Supply chains matter. The plumbing of global commerce has rarely been a topic of much discussion in newsrooms or boardrooms, but the past two years have pushed the subject to the top of the agenda. The COVID-19 crisis, postpandemic economic effects, and the ongoing conflict in Ukraine have exposed the vulnerabilities of today’s global supply chains. They have also made heroes of the teams that keep products flowing in a complex, uncertain, and fast-changing environment. Supply chain leaders now find themselves in an unfamiliar position: they have the attention of top management and a mandate to make real change.

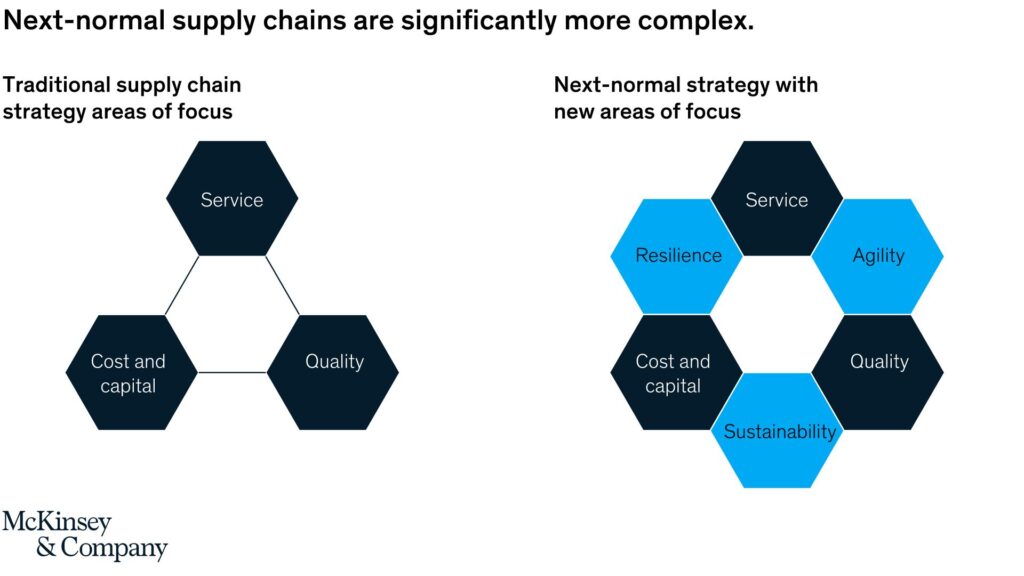

Forward-thinking chief supply chain officers (CSCOs) now have a once-in-a-generation opportunity to future-proof their supply chains. And they can do that by recognizing the three new priorities alongside the function’s traditional objectives of cost/capital, quality, and service and redesigning their supply chains accordingly.

The first of these new priorities, resilience, addresses the challenges that have made supply chain a widespread topic of conversation. The second, agility, will equip companies with the ability to meet rapidly evolving, and increasingly volatile, customer and consumer needs. The third, sustainability, recognizes the key role that supply chains will play in the transition to a clean and socially just economy.

Boosting supply chain resilience

Supply chains have always been vulnerable to disruption. Prepandemic research by the McKinsey Global Institute found that, on average, companies experience a disruption of one to two months in duration every 3.7 years. In the consumer goods sector, for example, the financial fallout of these disruptions over a decade is likely to equal 30 percent of one year’s EBITDA.

Historical data also show that these costs are not inevitable. In 2011, Toyota suffered six months of reduced production following the devastating Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. But the carmaker revamped its production strategy, regionalized supply chains, and addressed supplier vulnerabilities. When another major earthquake hit Japan in April 2016, Toyota was able to resume production after only two weeks.

During the pandemic’s early stages, sportswear maker Nike accelerated a supply chain technology program that used radio frequency identification (RFID) technology to track products flowing through outsourced manufacturing operations. The company also used predictive-demand analytics to minimize the impact of store closures across China. By rerouting inventory from in-store to digital-sales channels and acting early to minimize excess inventory buildup across its network, the company was able to limit sales declines in the region to just 5 percent. Over the same period, major competitors suffered much more significant drops in sales.

Supply chain risk manifests at the intersection of vulnerability and exposure to unforeseen events (Exhibit 2). The first step in mitigating that risk is a clear understanding of the organization’s supply chain vulnerabilities. Which suppliers, processes, or facilities present potential single points of failure in the supply chain? Which critical inputs are at risk from shortages or price volatility?

Read more at Future-proofing the supply chain

Subscribe us to get updates and leave your opinions in the comment box below.